Like all bits of process or procedure, it started with good intentions. With 4 Scrum teams all working on the same product and following the LeSS framework, we needed a Definition of Done that everyone could agree to. A set of standards that would make sure that every feature we delivered was to high minimum level of quality. However, a few months later and after seemingly endless “come-if-you-care” meetings in the breakout area, it was clear that our Definition of Done was causing us significant pain.

Boot Camp

The first draft of our Definition of Done was put together collaboratively at an off-site agile boot camp, set in the beautiful surroundings of Gatton Park on the edge of the North Downs. Unfortunately trouble was already brewing, and the scene inside the venue was looking a lot less idyllic. As a whole department we had a say on what criteria should go in to this DoD. Unfortunately the session ended on a long, and probably pointless, debate on what unit test coverage percentage we should specify in this new DoD. The purists said we should aim for 100%, the pragmatists thought the 85% currently specified by our static analysis tools would be more more achievable, and everyone else just wanted to go home after a long day. In the end discussions were brought to a close by the session lead declaring that anyone who wanted to argue their case further should stay behind at the end of the day. Needless to say, no one did and it stayed at 85%.

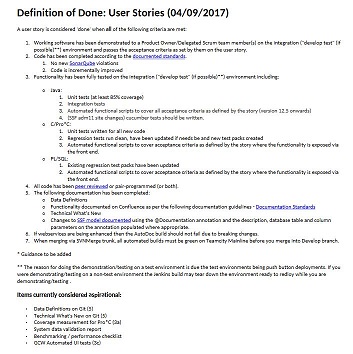

A few months on this DoD now looked a bit like this:

With multiple levels of bullet points, 2 levels of asterisks and a section for “aspirational” items, it was getting harder and harder to tell whether or not a user story was done. With the added pressure of teams, quite rightly, calling each other out in sprint reviews if they hadn’t met the criteria above, this meant that we ended up having a lot of “come-if-you-care” meetings to discuss whether a story could be considered done or whether a new exception case should be added.

It was the strict and specific nature of our DoD that had meant that a lot of these special cases had been introduced. If, for example, a team worked on a user story that was simply configuration changes, then did they need to write UI tests? If a change touched some old code with low unit test coverage, then did we need to write new tests so that all the legacy code could pass the coverage percentage specified? Additionally as some of our test tooling was still in it’s infancy, some levels of testing proved to be prohibitively expensive in particular areas - hence the “aspirational” items".

It was becoming clear that with all these meetings our DoD was slowing us down and causing unnecessary pain. Additionally, the effort required to tick a feature off as complete was increasing and this was threatening to undermine the entire thing. So what did we do?

A Better Way

Fed up of the endless meetings and pointless debates over specifics such as test coverage percentage, I set about getting a new DoD introduced. This DoD would, instead of mentioning specifics, set out high level objectives and then inform people of the intention behind these objectives. The idea being that instead of being incredibly specific and requiring all sorts of caveats, it would inform people of the reasons behind each criteria and empower them to make their own judgement calls.

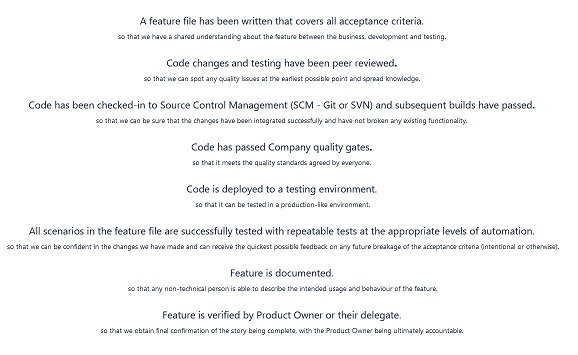

After canvassing ideas from Scrum Masters, Product Owners and running a workshop at one of our monthly community day, something similar to the following was agreed upon:

This new DoD didn’t contain specifics for unit test coverage, or which documentation should be written, but instead set out a number of high level objectives that all stories should meet. Each headline statement is then followed by a short “so that” statement explaining the intent behind the objective. Additionally a couple of supplementary pages entitled “What tests should I write?” and “What documentation should I write?” where published to provide guidance on what tests and documentation were appropriate for different scenarios.

The Results

I’d love to say that with the new DoD in place, that we no longer have meetings and long debates on whether certain stories are complete. We still have these every now and then, but I’d like to think the tone of these meetings has changed. With the DoD inspiring common sense and empowering teams to make their own judgement calls our debates are no longer about trivial matters such as whether we should have 85 or 90% code coverage, but instead are informed debates about what compromises we should make in the continued struggle between agility and quality.

You’ll also notice that we haven’t added asterisks or aspirational items. The DoD has remained largely the same (although teams are still encouraged to take ownership of it and update it where necessary). This has meant that what we do have is easier to follow. It is now much easier to determine whether or not an item can be considered done, often without even needing to refer to the DoD.

Overall it has reduced the amount of pain experienced when trying to complete a user story. It is by no means perfect, but in the scenario of multiple cross-functional teams all working on the same product, I’m not sure you can ever produce something that everyone will agree with that will cover every possible scenario. I’m happy to be proved wrong though.